A Timeline history of the Violin Bow - from c. 1600 - 1800

The Development of the Violin Bow

This essay is still in development ... not finished!!!

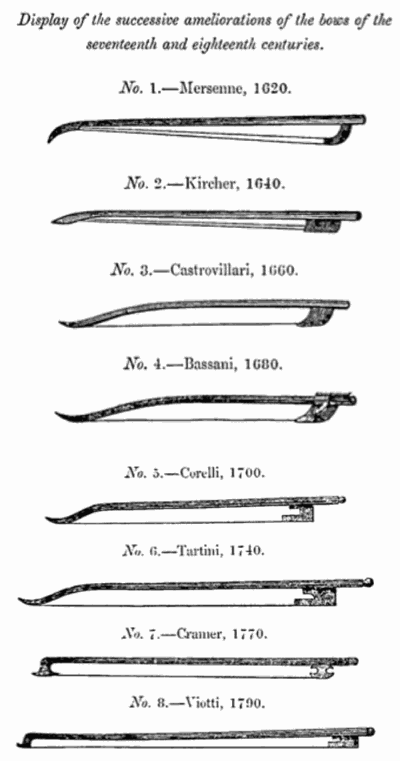

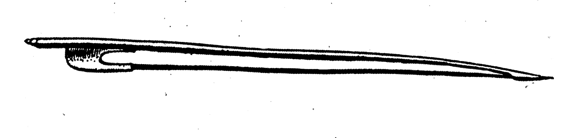

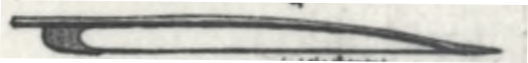

The basic differences between the modern (Tourte) bow, and the baroque bow are well known - a convex curve and light curved tip with the hair ever closer to the stick being the defining features of the baroque bow. While this is in principle accurate, the significance lies in the details. During our period the bow was in constant development (arguably more so than the violin itself), and the differences (with associated differences in playing technique) have an enormous impact on sound and articulation. This diagram, from Stradivarius by F.J. Fétis, Paris 1856, shows somewhat schematically the “improvement”. Unfortunately, his accompanying commentary is mind-bogglingly inaccurate and opinionated but simultaneously worryingly influential in its establishment of unfounded tradition (quoted here in a translation by John Bishop, 1861):

At this period [17th-century], the head was always very elongated and ended in a point which turned back a little. The stick was always more or less bent (‘bombée’). Such was the bow of Corelli and that of Vivaldi. These two masters, who lived at the commencement of the 18th-century, had not yet experienced the necessity of rendering the stick flexible, because they had no idea of imparting to their music the varied shades of expression [of more modern times]: they were acquainted with but one sort of conventional effect, which consisted in repeating a phrase piano, after it had been played forte. It is a remarkable thing, that the construction of bow-instruments had arrived at the highest point of perfection, whilst the bow itself was still relatively in a rudimentary state... The violinist Woldemar ... made a collection of bows of the celebrated ancient violinist of Italy; he gave engravings of those ... in his Method for the Violin, which met with no success and which is now unfortunately of excessive rarity ... The result of all the information ... is that no serious attempt was made to improve the bow, until towards the middle of the eighteenth century.

Hmm - perhaps an interesting window into mid-19th century thought, but to the extent that this became received opinion, it's dangerous nonsense!

But the thing is, that laying aside Fetis' annoying value-judgements, his diagram was not so far wrong. The bow indeed went from short to longer, the outward curve changed over time to the inward camber of the Tourte bow. The number of hairs increased, and the method of fixing the hair became ever more sophisticated and flexible. And quite apart from Fetis' ridiculous promotion of the 'echo' as the fundamental baroque dynamic and his preposterous assertion, that "they [Corelli, Vivaldi et al] had no idea of imparting ... varied shades of expression", there is Fetis' contention that "the construction of bow-instruments had arrived at the highest point of perfection, whilst the bow itself was still relatively in a rudimentary state". Is it likely that the instruments (Amati, Stradivarius etc) and the music they were used to play (Corelli, Biber, Bach) should have reached 'perfection', and the bows not? No, surely not. I think we can assume that the bow at any given point in time did exactly what was required.

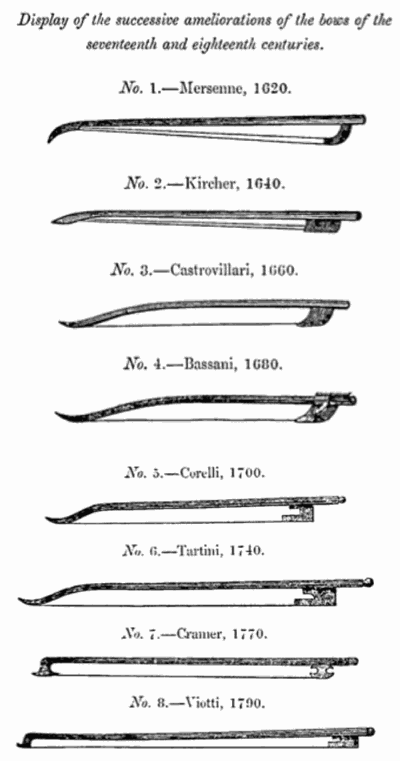

But, by the way, it is worth pointing out that Fetis's depiction of the bows of Mersenne (No. 1, 1620) and Kircher (No. 2, 1640) are not the only illustrations they respectively supply. Mersenne's image reproduced by Fetis comes from Page 178, Chapter 4 next to a pochette. A few pages later, on page 184, in his discussion of the whole violin ensemble, his illustration of the bow is somewhat different:

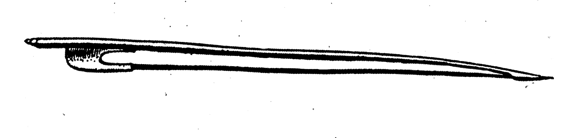

I have not found Kircher's illustration used by Fetis, but this is from Book VI, Plate 8, Folio 487 in Kircher's Musurgia Universalis (Rome, 1650);

These two look more like what we see in the paintings.

Getting back to the task at hand, being precise about the development of the bow, and its state at any given moment is not an easy task. There are very few extant old bows, and it's very difficult to date those that did survive (in organ lofts, sculptures, mis-appropriated for other stick-like uses etc.). Moreover, we don't know if these few surviving bows are representative - or if they were put 'out of the way' because they weren't useful! Even as we get into the late 18th-century, there is still plenty of uncertainty. Makers only sometimes stamped their bows, and never dated them. (For example, every bow by the French maker Meauchand was apparently made in 1775!!) So research has to be extended to include iconography and the few mentions of bows in the sources.

The early paintings (from the first half of the 17th-century) show remarkably consistently a short bow - pretty much the length of the violin - in essentially three categories of form:

school of Carravagio, Italy 1590?

Domenico Zampieri, Italy 1620

Il Guercino, Italy 1620

Judith Leyster, Holland 1630

Carravagio, Italy 1595/6

Spada, Italy c. 1615

Molenaar, Holland 1629

Claesz, Holland 1623

Gentileschi, Italy 1624

Sorgh, Holland 1645

Gabbiani, Italy 1685

Honthorst, Holland 1626

I have selected but a few pictures here - always a procedure to be wary of, as this division of categories is much less clear cut than I make out - just as an example, here is a detail from a rather lovely painting by Gerrit van Honthorst in 1626, where the bow is somewhere between straight and elegantly sweeping:

Not only are all the bows short, but it's also worth noticing their thickness and colour - many of them seem both too light-coloured and too thick to be made from snakewood (commonly assumed to be the wood for baroque bows) - in fact, what we see in these 17th-century paintings suggests to me indigenous woods, like plum, beech, larch, cherry, yew etc. etc.

So much then for the iconographical evidence from the 17th-century. From the written sources we have close to nothing about the form, structure or material of the bow. What little we do have is frustratingly imprecise, but certainly has nothing to contradict what we have seen in the paintings. We have the illustrations to the texts of Mersenne, Praetorius and Kircher. The bow is certainly not longer than the violin, and has a familiar form. Mersenne specifies that the bow is made of wood (!) - and has between 80 and one hundred hairs. Kircher, discussing the Viol (which apparently includes the violin) mentions - "which is sounded with a plectrum or bow made of horsehair".

Towards the end of the century, we have a few slightly more specific mentions concerning length.

Roger North mentions Nicolai Matteis more than once;

But "very long" is not really very precise. In "Notes of Comparison between the Elder and Later Musick and Somewhat Historicall of both [c. 1726]", North writes (again, of Matteis);

Well, "as long as for as Base Violl" is indeed extremely long - especially if we take Christopher Simpson's 1665 description of a "Viol Bow for Division" as relevant;

Elsewhere North writes:

Apart from the wonderful evocation of an extremely rhetorical performing style, bipedelian means two feet long = 61 cm, which is more consistent with our other sources.

In his little tutor, The Gentleman’s Diversion from 1693, John Lenton writes:

Another invaluable source is John Talbot' Manuscript (1685 - 1701). In this we have some rather painstaking measurements of various instruments, including the violin and bow. In his table of the essential dimensions/measurements of the violin he writes that "the usual length of the Consort Bow" is two feet (61 cm), whereas "The length of the Bow for Solo's or Sonata's" is between 2'2" and 2',3" - translating to 66 to 68.58cm. A couple of paragraphs later he writes:

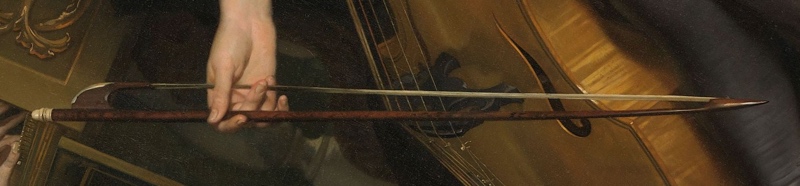

This is the first specific mention of snakewood as the type of wood ... although in his Traité des instruments de musique (c.1631) Pierre Trichet suggests that bows of "brazilwood, ebony ... and other solid wood, are the best ..." . The first unequivocally snakewood bow from our iconographical evidence is in David Leeuw with his family, by Abraham van den Tempel from 1671. (The picture in its entirety is in the Rijksmuseum, and can be viewed by clicking on this detail of the bow itself)

But while we're wondering about material and length, it's also worth looking again at a rather wonderful painting by the French artist Nicolas Tournier. From before 1639 (when he died) it depicts a surprisingly long bow, which in its colour and elegantly thin tip suggests it could be made of snakewood - or ebony, or some lighter stained wood. Click on this detail for the full picture.

Snakewood is recognised these days as the wood for baroque bows. It has huge advantages - it's lovely to work with, it holds its form and elasticity extremely well, it's sufficiently dense to allow extremely fine thin sticks. And indeed, as we move into the 18th-century it seems to become more and more common. But as already mentioned the colour and dimensions of many (most?) of the bows in 17th-century paintings suggest indigenous wood.

What were they like? How did they work? Well, on one level, we can never know - and as I have already pointed out, there are as good as no surviving examples. But we can reconstruct, and in my attempt to better understand the 17th-century, I have actually started making such short, light bows - you can read about my thoughts, the process and the results on my Historical Bows page. What is immediately clear is that short bows made with indigenous woods have their own advantages - they are 'faster', they articulate with a lovely soft clarity, the sound has a feeling of space around it, somehow more 'human' than the slightly harder snakewood sound. As discussed in my essay on bowing technique, they are invaluable in understanding 17th-century music and the 17th-century written sources.

It would be ambitious from the evidence so far to extrapolate an evolution - although it is noticeable, I think, that the later paintings in the 17th-century begin to include ever longer bows As we move into 18th-century paintings and illustrations, we see the bow gradually becoming longer, and increasingly (the later we go) with a more pronounced reverse camber. (This, I must again emphasise, is only a tendency. We continue to see short bows illustrated quite late, just as we also saw (rather less often) some surprisingly early longer bows):

Michel Corette, 1738

Veracini, 1744

Here we also see the limits of iconographic evidence - the same artist, revisiting the same subject 12 years distant portrays in the earlier painting an extremely short bow ('guesstimate' around 54 cm), with a simple straight form, and in the later a considerably longer (68cm?) bow, with a slightly elevated tip.

Gerrit Dou, Holland 1653

Gerrit Dou, Holland 1665

In 1741, in a letter home to his family, the young English aristocrat Benjamin Tate, on a then fashionable "Grand Tour" writes;

As we move later into the second half of the 18th-century there seem to be many fewer paintings, but written sources (treatises, instruction manuals etc) become ever more precise - at least about technique (see the essay on Bowing technique). Concerning the bow itself we begin to have ever more actual bows that have survived, and can be more reliably dated. For the time being, as we move into the era of the screw-frog, the pre-classical and classical bow, I leave off - a very good place to start is the two Articles by Robert Seletsky; New Light on the old bow Part 1 (Early Music 32/2, pp. 286-301) and Part 2 (Early Music, 32/3, pp. 415-26).

But, by the way, it is worth pointing out that Fetis's depiction of the bows of Mersenne (No. 1, 1620) and Kircher (No. 2, 1640) are not the only illustrations they respectively supply. Mersenne's image reproduced by Fetis comes from Page 178, Chapter 4 next to a pochette. A few pages later, on page 184, in his discussion of the whole violin ensemble, his illustration of the bow is somewhat different:

These two look more like what we see in the paintings.

Getting back to the task at hand, being precise about the development of the bow, and its state at any given moment is not an easy task. There are very few extant old bows, and it's very difficult to date those that did survive (in organ lofts, sculptures, mis-appropriated for other stick-like uses etc.). Moreover, we don't know if these few surviving bows are representative - or if they were put 'out of the way' because they weren't useful! Even as we get into the late 18th-century, there is still plenty of uncertainty. Makers only sometimes stamped their bows, and never dated them. (For example, every bow by the French maker Meauchand was apparently made in 1775!!) So research has to be extended to include iconography and the few mentions of bows in the sources.

The early paintings (from the first half of the 17th-century) show remarkably consistently a short bow - pretty much the length of the violin - in essentially three categories of form:

First are the highly arched bows -

often with the hair fastened at the tip with what looks like a knot and cap. Here's a short selection of details;

school of Carravagio, Italy 1590?

Domenico Zampieri, Italy 1620

Il Guercino, Italy 1620

Judith Leyster, Holland 1630

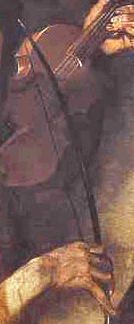

The next category consists of almost straight bows -

one can see that the stick itself is almost straight, remaining relatively thick throughout its length, resulting in a sort of elongated triangle with the hair;

Carravagio, Italy 1595/6

Spada, Italy c. 1615

Molenaar, Holland 1629

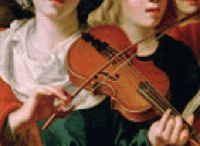

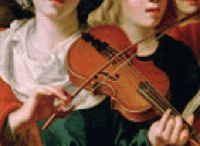

And the last a more "sophisticated" form -

with an elegant sweep towards the tip. As one would expect to get this graceful curve, the stick is more tapered towards the tip than in the other two forms.

Claesz, Holland 1623

Gentileschi, Italy 1624

Sorgh, Holland 1645

Gabbiani, Italy 1685

Honthorst, Holland 1626

I have selected but a few pictures here - always a procedure to be wary of, as this division of categories is much less clear cut than I make out - just as an example, here is a detail from a rather lovely painting by Gerrit van Honthorst in 1626, where the bow is somewhere between straight and elegantly sweeping:

Not only are all the bows short, but it's also worth noticing their thickness and colour - many of them seem both too light-coloured and too thick to be made from snakewood (commonly assumed to be the wood for baroque bows) - in fact, what we see in these 17th-century paintings suggests to me indigenous woods, like plum, beech, larch, cherry, yew etc. etc.

So much then for the iconographical evidence from the 17th-century. From the written sources we have close to nothing about the form, structure or material of the bow. What little we do have is frustratingly imprecise, but certainly has nothing to contradict what we have seen in the paintings. We have the illustrations to the texts of Mersenne, Praetorius and Kircher. The bow is certainly not longer than the violin, and has a familiar form. Mersenne specifies that the bow is made of wood (!) - and has between 80 and one hundred hairs. Kircher, discussing the Viol (which apparently includes the violin) mentions - "which is sounded with a plectrum or bow made of horsehair".

Towards the end of the century, we have a few slightly more specific mentions concerning length.

Roger North mentions Nicolai Matteis more than once;

"He was a very tall and large bodyed man, used a very long bow, rested his instrument against his short ribbs".

But "very long" is not really very precise. In "Notes of Comparison between the Elder and Later Musick and Somewhat Historicall of both [c. 1726]", North writes (again, of Matteis);

He was a very robust and tall man, and having long armes, held his instrument almost against his girdle, and his bow was long as for a base violl, and he touched his devision with the very point;”

Well, "as long as for as Base Violl" is indeed extremely long - especially if we take Christopher Simpson's 1665 description of a "Viol Bow for Division" as relevant;

"Its length (betwixt the two places where the Hairs are fastened at each end) about seven and twenty inches".

This is 68.6 cm hair length, which must give you a bow around 76cm at the shortest. That's longer than a modern bow, which seems inconceivable. Elsewhere North writes:

"Old ... Matteis used this manner ['Stoccata'] to set off a rage, and then a repentance; for after a violent stoccata, he entered at once with the bipedalian bow, as speaking no less in a passion, but of the contrary temper"

Apart from the wonderful evocation of an extremely rhetorical performing style, bipedelian means two feet long = 61 cm, which is more consistent with our other sources.

In his little tutor, The Gentleman’s Diversion from 1693, John Lenton writes:

"let your Bow be as long as your Instrument, well mounted and stiff Hair'd, it will otherwise totter upon the String in drawing a long stroke".

This is very useful - not only does he specify the length, but he wants it well-tensioned. This is also implied by Falck; "... so that the hair, well drawn, achieves a full stroke and sound from the strings..."

Another invaluable source is John Talbot' Manuscript (1685 - 1701). In this we have some rather painstaking measurements of various instruments, including the violin and bow. In his table of the essential dimensions/measurements of the violin he writes that "the usual length of the Consort Bow" is two feet (61 cm), whereas "The length of the Bow for Solo's or Sonata's" is between 2'2" and 2',3" - translating to 66 to 68.58cm. A couple of paragraphs later he writes:

"Bow of fine Speckled-wood has two mortises to wch [which] the hair fastened and one at the head the other towds [towards]the bottom or back part of Nutt. Hair of the best & finest white hair if possible from Stoned horse: hair should be full. Bow of violin not under 24' from there to 27 1/2 at most. 27, 26-25 1/2 Solo-Bow." So that's not under 61cm, up to 70cm at most, 68.6 to 64.77 for a solo bow.

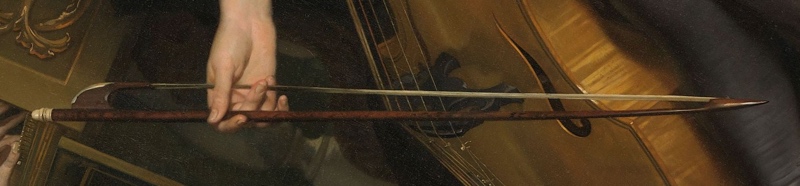

This is the first specific mention of snakewood as the type of wood ... although in his Traité des instruments de musique (c.1631) Pierre Trichet suggests that bows of "brazilwood, ebony ... and other solid wood, are the best ..." . The first unequivocally snakewood bow from our iconographical evidence is in David Leeuw with his family, by Abraham van den Tempel from 1671. (The picture in its entirety is in the Rijksmuseum, and can be viewed by clicking on this detail of the bow itself)

But while we're wondering about material and length, it's also worth looking again at a rather wonderful painting by the French artist Nicolas Tournier. From before 1639 (when he died) it depicts a surprisingly long bow, which in its colour and elegantly thin tip suggests it could be made of snakewood - or ebony, or some lighter stained wood. Click on this detail for the full picture.

Snakewood is recognised these days as the wood for baroque bows. It has huge advantages - it's lovely to work with, it holds its form and elasticity extremely well, it's sufficiently dense to allow extremely fine thin sticks. And indeed, as we move into the 18th-century it seems to become more and more common. But as already mentioned the colour and dimensions of many (most?) of the bows in 17th-century paintings suggest indigenous wood.

What were they like? How did they work? Well, on one level, we can never know - and as I have already pointed out, there are as good as no surviving examples. But we can reconstruct, and in my attempt to better understand the 17th-century, I have actually started making such short, light bows - you can read about my thoughts, the process and the results on my Historical Bows page. What is immediately clear is that short bows made with indigenous woods have their own advantages - they are 'faster', they articulate with a lovely soft clarity, the sound has a feeling of space around it, somehow more 'human' than the slightly harder snakewood sound. As discussed in my essay on bowing technique, they are invaluable in understanding 17th-century music and the 17th-century written sources.

It would be ambitious from the evidence so far to extrapolate an evolution - although it is noticeable, I think, that the later paintings in the 17th-century begin to include ever longer bows As we move into 18th-century paintings and illustrations, we see the bow gradually becoming longer, and increasingly (the later we go) with a more pronounced reverse camber. (This, I must again emphasise, is only a tendency. We continue to see short bows illustrated quite late, just as we also saw (rather less often) some surprisingly early longer bows):

Michel Corette, 1738

Veracini, 1744

Here we also see the limits of iconographic evidence - the same artist, revisiting the same subject 12 years distant portrays in the earlier painting an extremely short bow ('guesstimate' around 54 cm), with a simple straight form, and in the later a considerably longer (68cm?) bow, with a slightly elevated tip.

Gerrit Dou, Holland 1653

Gerrit Dou, Holland 1665

In 1741, in a letter home to his family, the young English aristocrat Benjamin Tate, on a then fashionable "Grand Tour" writes;

"[Locatelli] plays with a Short Bow, and the Reason He gives for Doing so, is, that He Believes, no Fidler can Play any thing with a Long Bow, that he can't play with a Short one."

(As an aside here, it's maybe worth pointing out that we have it from various sources that Locatelli's sound left something to be desired. That would certainly add up with his professed like of a shorter bow, the characteristics of which - in my experience - favour articulation at the cost of a singing sound and longer line. ([he] "mainly sought to astound the listener with his scratchy playing" (J.W.Lustig, 18th-century Dutch organist).

As we move later into the second half of the 18th-century there seem to be many fewer paintings, but written sources (treatises, instruction manuals etc) become ever more precise - at least about technique (see the essay on Bowing technique). Concerning the bow itself we begin to have ever more actual bows that have survived, and can be more reliably dated. For the time being, as we move into the era of the screw-frog, the pre-classical and classical bow, I leave off - a very good place to start is the two Articles by Robert Seletsky; New Light on the old bow Part 1 (Early Music 32/2, pp. 286-301) and Part 2 (Early Music, 32/3, pp. 415-26).

© Copyright 2020 by Richard Gwilt. All Rights Reserved.